|

|

Judy writes about dance lighting:

|

|

Introduction:

|

The basic aims in dance lighting are the same as for any lighting - selective visibility, indication of time and place if necessary,

enhancement of scenery and costumes, conveying the general message of the piece, and so on. As usual the complexity lies in the details.

For example, "selective visibility" means you have to decide just what needs to be seen. In most dance styles, movement of the body

is more important than facial expression, for instance. In almost all dance, the pattern of movement on the stage is meaningful,

while in drama it is usually less so.

Another major difference is that often there's no scenery. It's up to the lighting designer to create a visual composition on the stage. The

problem is that, unlike theater, usually you need to illuminate the whole stage because the dancers don't confine themselves to a small region.

So, you need to find methods for creating a composition and atmosphere that still let you light up the entire area.

In lighting dance there are two major questions you must answer before anything else: First, what style does this dance belong to? Is it

classical ballet, modern ballet, classical modern (Graham type for instance), "postmodern"? Second, is the lighting within a repertory plot

or will it stand on its own. A relatively short dance might be performed together with other pieces from the company's repertory, where the

other pieces could vary on different evenings. The company would generally have a standard lighting plot that the designer needs to stick to,

though you can add a number of extra instruments for specials - depending on the company's resources and number of electricians. But there are

also full length dance pieces, where you might not be required to stick to the standard lighting plot. Again, this depends on the company's

program, needs, and performance schedule.

Here I'm going to talk first about different styles, and then I'll describe a basic repertory plot, because that will give a good general

overview of the angles and techniques that are useful in any kind of dance lighting.

|

|

Styles:

|

Dance styles can be very loosely broken up into classical ballet, modern and post-modern. The best way to understand this is to compare the

two photos below. The first is from a classical ballet, the second modern. They're both dance, but obviously the lighting for the first

wouldn't work for the second, or vice versa!

|

|

|

The Nutcracker - Ashland Regional Ballet

|

The Earth and Me - Shadow Box Theatre

|

|

Classical: Classical ballets very often have story lines, and the dancers represent real (or magical or imaginary) people.

Therefore in classical ballet facial expression is often important, as opposed to other more abstract styles. More

naturalistic colors may be used for the light, and less saturated color, except for special moments which involve the

supernatural, or something non-realistic. So many ballets involve ghostly romantic figures that blue is very common,

and there's even a special tint called "Giselle Blue!"

|

|

|

Les Sylphides - Peoria Ballet

|

|

There are also technical demands in classical ballet which cannot be ignored. It is often very

important not to blind the dancers with low sidelight angles, because classical technique

involves movement where it's difficult and crucial for the dancer to keep on balance, and that's

much, much harder if light suddenly hits your eye as you turn, for instance. Another interesting

issue is that because the dancers are usually on pointe (wearing toe shoes and balancing on their toes),

it is very important for them to see the floor - they have told me that otherwise they feel disconnected

from the ground and it's harder to keep their balance. Look at the photo of this classical duet: you can

see the dancers' movements are emphasized by the side lighting, but the floor is well lit:

|

Rubies - Purchase College

Conservatory of Dance

|

|

|

Modern: Lower and more expressive angles are often used. More saturated color might be used, since the dancers often

play a more abstract role. Usually there are no naturalistic constraints, and the difficulty is to find a concept for the

lighting. Tom Skelton, a marvelous and well known designer of dance lighting, once said that he looks for the moment in the

dance that makes the strongest impact on him, and uses that as a key to build everything else around. Jean Rosenthal did

lighting for Martha Graham's work (one of the key founders of modern dance), and almost all the works had a key light

coming from a high up diagonal. She called it "Martha's eye of God," and it expressed the strong abstract spiritual

dimension of the works.

Post-modern: Lighting for contemporary dance often goes against traditional methods intentionally, to jar the

audience and create a generally powerful atmosphere. Fluorescent lights might be used, or video panels, or a general

wash as if this were not a theatrical event at all. In this case often it is more important to create the desired

atmosphere than to highlight the physical movements of the dancers, or see their faces. Bill Forsythe, a wonderful

and renowned choreographer, used six HMI fresnels as toplights in a dance, with no cues at all. The dancers performed

in a general cool wash from above which did not illuminate their faces and did not bring out their movements or any

pattern of movement or position onstage at all. However, the effect was startling and powerful because of the still,

cold enveloping feeling this engendered. It's quite common today to fill the air with smoke and sharp beams of light,

as if it were a rock concert. This gives the dance a modern feeling which is nice and gives it appeal to younger

audiences, but needs to be used with thought and not indiscriminately.

|

|

|

Functions of Light:

|

Let's go over the general functions of light, and then the characteristics of light, from the point of view of dance

lighting: Most are the same as for theater, but there are a few differences or points to think about:

- Selective visibility: Here the main thing is almost always the dancer's movement, and the grouping of

dancers on the stage. Movement is best lit from the side. If you can, do an experiment: light a friend from one side

only and have them hold up an arm. You'll see the arm outlined on one side as if the shape of the movement is being

drawn. Have the friend turn around. You'll see their face alternately dark and light. Now do the same thing when they're

lit from the front, or from straight above. The movement isn't outlined, and you won't see any difference in them as they turn.

The angle doesn't highlight or emphasize the movement at all. For this reason, the basic angle for dance lighting is always from

the side. This is in contrast to theater where the basic angle for visibility is from the front.

- Time and place: This depends on the dance itself: classical story ballets will have a specific time and place

(a forest at night, a lake side, a majestic ball), abstract dances might not. As with theater, it can be helpful to imagine for

yourself a time and place even if one isn't specified - what kind of place does it feel like this dance takes place in? (that's also

a useful question to ask the choreographer, and might prompt him to talk about the dance itself rather than telling you where he wants

spotlights!) You could use gobos to create a time and place perhaps, or color to clarify it, or it could just help you to develop a

clear concept for yourself.

|

Home - Adrienne Celeste Fadjo Dance

|

- Mood and atmosphere: These depend on the dance. There is no written text to help you get the mood,

and it's not easy to grasp in rehearsal where the dancers are working hard on technical difficulties. Often you can

grasp the mood from the music that is chosen. If not, it's helpful to ask the choreographer things like "if you could

make a movie of this dance, what kind of place would you set it?" and that could indicate the kind of atmosphere he has in mind.

- Heightening effect of other visual elements: Costumes are absolutely crucial here!! Often there won't be scenery

in a dance performance, and the most powerful visual element on stage will be the costumes. You absolutely have to know exactly what

the dancers will be wearing, especially what colors and textures. Try and get samples of the cloth, and keep them with you when you're

thinking about what colors to use. The samples should be as big as you can get them, not tiny little snips.

|

|

Repertory Companies:

|

Repertory dance companies may do an evening of short pieces, which are not always the same, so that in some performances

they will do dances 1, 2 and 3, and in another performance they might do 1 and 3, but substitute something else for 2. A

company might have fifteen such dances in their repertory at a time, and could switch them around depending on various

considerations such as scheduling, needs of dancers and marketing purposes. Such a company will have a general repertory

plot suitable for all dances, and the designer of a new dance will need to work within that plot, while being free to change

some of the color filters (or all of them, time permitting, since it's done in the intermission), and add various special

extra instruments for that dance. See "rep plot" section below.

A company that usually does repertory might also do a full length work; for instance classical ballet companies that often

do rep are almost certain to do a version of Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker around Christmas time! In that case there's

no need to stick to the rep plot, of course.

|

The Nutcracker - Ashland Regional Ballet

|

Repertory Plot:

Low sidelights: This is the basic angle for lighting dance. Any dance setup will have lighting positions

("booms") along the side of the stage (usually four or five such booms on each side, depending how deep the stage

is.) These will each have anywhere between three and twelve instruments on them, depending on the company resources.

There are a few basics here that even a simple layout would have:

Some or all of the sidelights in a rep plot would have their colors changed between dances, in intermission.

In a plot that's not too big, and without a lot of technicians, the top instruments might have a cool circuit

(usually the highest) in some kind of light blue, and a warm circuit beneath that. Then there could be a circuit

just above head height with color changes.

|

Aubade - Dance as Ever

The dancer is lit in contrasting colors from the two different sides.

The sidelights are from a sufficiently low angle not to light the floor.

|

Another very basic element on booms are the "shin busters," which are down near floor level. These are

effective because they let you light the dancer without lighting the floor, so you can have light dancers

moving around a deeply colored floor. In classical ballet, even when the whole stage is very light and natural,

the shins are useful for bringing out costume colors.

Today there are often enough dimmers to provide a dimmer for each lamp. If not, sidelights are circuited in two different ways,

depending on the company and the designer of the rep plot. Usually some of the boom circuits are done one way, and the others in the

second way. The first way involves dividing the stage into strips, so that for instance, channels 1-5 might be the top (cool colored)

circuit, where channel 1 is the top instrument on each of the downstage booms, channel 2 is the top instruments on the next pair of booms upstage

from that, etc. This will allow you, for instance, to darken the upstage and focus on dancers in front.

The second way has different sides with different circuits, so that a circuit on the two booms downstage left are wired together

(channel 6) and the two booms downstage left could be channel 7, and so on. It's very effective to light a dancer with different intensity

(or different color!) from the two different sides.

Many companies have a diagonal element as well: a lamp on each of the upstage and downstage booms, around head height, focused on the

diagonal from one corner of the stage to that opposite. This helps bring out, or isolate, a dancer moving along the diagonal.

High sidelights: These are from overhead pipes, and they're useful for getting light onto the dancers'

faces without flooding them from the front, so that you keep the expressiveness of the movement but gain some facial visibility.

Color wash: These could be from the front of house, as well as the first electric, and perhaps another

one further upstage if the stage is deep - they provide visibility but are usually less important than the sidelights, because they're not

expressive and don't bring out the movement.

Pools: A rep plot might have a series of 9 to 25 profile spots that give round pools of light, breaking

up the stage into a sort of grid. This is because in any dance there could be a need to isolate a solo, or maybe several dancers in different

places, and the grid of pools provide a ready made possibility to do that anywhere on stage without needing special instruments for each dance.

Remember that top lights don't bring out movement or facial expression, but they're great at pinpointing location.

Backlight: There are two basic kinds of backlight: straight and diagonal. The effect is just like in theater:

diagonal light gives a bit more visibility and also emphasizes diagonal movement. Straight backlight thrusts the dancers forward, and is good for

saturated color.

Cyc: Almost every rep company will use a cyc at times, and the plot would have to have cyclorama lighting.

Other effects: Gobos are really effective in dance lighting! They let you draw a pattern on the stage,

they're powerful in creating mood, and also effective on a cyc.

|

|

The Earth and Me - Shadow Box Theatre

|

Ballet lighting very frequently uses follow spots, these might be the hard kind used on singers, which totally isolate the dancer, but in

recent years a softer field of light is preferred, bringing out the dancer without locking him/her into an artificial circle.

Another element that has become very fashionable is footlights, striplights across the front of the stage.

|

|

|

Rehearsal and Cues:

|

- Seeing rehearsal: Come to rehearsal with pages where you've already drawn lots of little squares, to mark the movements on.

This will help your focus in watching a rehearsal, and can also be a great help when talking with the choreographer, who will be

impressed that you know the movements of the dance so specifically.

- Ask for a recording of the rehearsal. Dance companies very often video runs-through so the dancers and choreographer can watch

their work and see what needs to be corrected. Watching this again at home will allow you to plan very precise cues in advance, complete

with timing. Since dance is generally to music, and if it's not a wealthy company this music is recorded, the timing will always be that

of the recording.

- How do you plan cues? Your concept might begin from a key moment in the dance, as Skelton discussed. It might relate to the kind of

time or place the dance could be happening in. A basic rule is to pay attention to movement patterns and think about the need for focus. Do

the dancers retreat to the rear plane of the stage? Does that mean the front should be darkened? Do they move on the diagonal? The lights

should NOT change all the time just to follow the dancers, but you will need to consider when it is important to zoom in to a dancer in a

particular area. Music generally gives good indications when a change is needed but again - you should not change the lighting every time

the music changes, but think carefully about the need for this.

- I learned from working with some very good people that the timing of lighting cues for dance should relate as carefully as possible

to the actual movement. You want the lights to look almost as if the movement made them happen. For instance, if you want the lights to

spread as the dancers move outwards from a small tight circle to the farthest corners of the stage begin the cue when they are in the circle,

and have the lights change along with their movement so that it's completed as they reach the furthest point. (This is, of course, a matter

of style - it might be appropriate to do a sharp cue that goes against the movement rather than with it!)

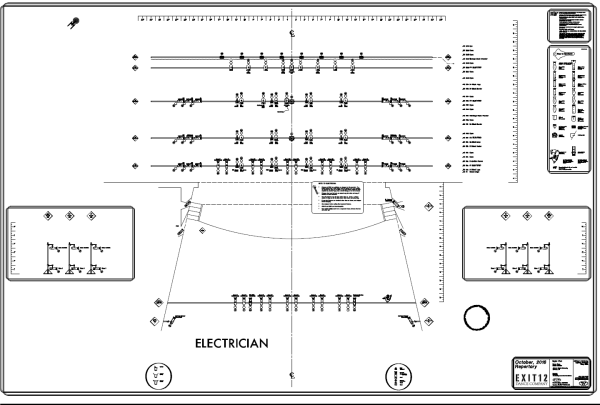

Here's a typical repertory plot for a medium sized dance company. Following the rep plot you'll find the magic sheet for that plot. The magic

sheet will make it easier for you to understand the different lighting elements, and indeed that's what we work with when we plot the cues.

Click on the images for larger, PDF versions.

|

Photographs and lighting designs by Jeffrey E. Salzberg

(Judy forgets to take photographs of her shows)

|

|